Blog: Why is it so challenging for fundraisers to move into senior level positions?

September 16, 2019

Blog: Uniting European fundraising for a stronger future

February 5, 2020The past twenty years have brought ‘seismic’ changes to the charity sector and the way it is perceived. Where the biggest brands had dominated the charity world, the public now wants to know more about what their money will get. Geneva Global’s Doug Balfour, explores what it takes to measure impact.

As I see it, the charitable world has seen three seismic shifts in the last two decades. A change in the type of donor and their expectations, a change in power and control to the donor and a subsequent, logical need for new impact measures.

Twenty years ago, the big charities were the ones with power, brand and they dominated the charity sectors. Donors supported their favourite causes – children, medical, development, emergency aid, and education charities – whilst overseas aid and corporate giving went to the usual, safe big charities.

During the decade I spent leading Tearfund UK (1994-2004), we saw a generational change – with the small donor proposition moving from “trust us and we’ll do a good thing” towards “I want to pick what my money goes to”.

Among other changes, the “donate” button started appearing on charity websites, and by 2005, organisations like Kiva and later Global Giving, were creating the first online giving platforms. With that shift came donors’ need to seek more information to choose what they wanted to support.

By 2010, major donors were giving away vast fortunes in their lifetimes. Corporations and even Western governments wanted a lot more say over what their money would fund and donors looked for choice, data and responsive reporting. Feedback and control shifted quickly to the donor side. The higher the gift size, the more that business-like impact measures were sought.

Social Impact Measurement hit the charity world with simple metrics at first, and then increasingly sophisticated data driven measures. But, what measures really matter?

Through Speed Schools, Geneva Global’s 10 month accelerated learning program, we can say that – over the past 7 years – we’ve given 200,000 Ethiopian primary age children a second chance at life, getting them back into government schools. Still, this doesn’t convey the full picture.

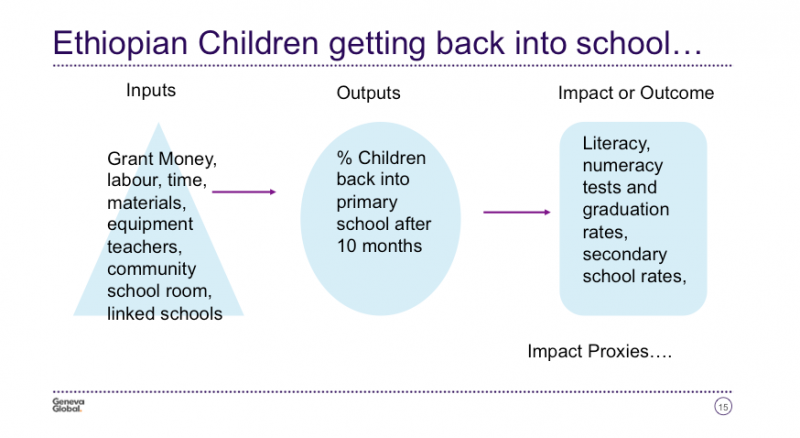

To do that, we measure a broad range of inputs, outputs and impact. Input is not simply the size of the donor money, but labour, expertise, teachers, supervisors, school rooms, furniture, teaching materials and a condensed curriculum. For output, we measure the intent of the programme – this might be the percentage of children successfully placed back into school by the end of a year.

Of course, what we ultimately look for is long-lasting, sustainable, significant, positive change in the primary target group of beneficiaries. This is our social impact. This can be difficult and expensive to collect, needs time, and can be hard to differentiate from other external influences.

In the case of Speed Schools, we’ve run a longitudinal study tracking the first cohort of children placed back into school in 2011 and followed their progress, comparing them to similar cohorts that had always been in the government primary school. We measure annual literacy and numeracy rates with standardised tests, grade and graduation achievement, secondary school entrants, household income studies and even the jobs and income levels they had 10 years later. That’s where we can see our impact.

This approach is expensive and not always feasible. But, there are impact proxies that can be used to avoid the need for a Randomised Control Test or large longitudinal study. Impact indicators that have been studied enough that it would be reasonable to accept them as indicators of longer-term impact.

An example would be a typical clean water programme in Africa. The activity indicator given is often the number of boreholes drilled and water pumps installed, but the sustainability factor is in how long these pumps continue to work. Impact proxies could be how many people live in a 1km radius of the pump or perhaps the decrease of diarrhoea and water borne diseases in local health centres serving that community from the date when clean water was made available.

Essentially, this means recognising that to the donor, their gift is an investment. Typically, at Geneva Global and Global Impact, we look at four levels of social measurement for clients. The first is individual project indicators (as above), then there’s portfolio achievement – how the project performs against its benchmark. You also need a value for money metric such as cost per life for anti-human trafficking, school re-entry or tropical disease prevention. And there needs to be a way of comparing social impact across sectors, geographies and even potentially to forecast the likelihood of success based on previous data.

The need for donor choice is not going away. The requirement for more robust social impact measurement will continue to grow and get more discerning. Donors are pushing for more co-creation between donors and grantees; donor collectives, systems change programs and philanthropic funds all exist because donors want to see more social impact for their money.

We still need high quality storytelling to touch the heart, but now are being required to demonstrate an equally compelling Social Impact story, with good, verifiable data to satisfy the head.

About Doug Balfour

Doug Balfour formerly served Tearfund – one of the UK’s largest aid agencies – for nine years as general director. He then went on to set up Geneva Global, a full-service social impact advisory, which he ran as CEO. Having recently merged the company with Global Impact to make up one of the largest philanthropic consultancies in the world, he has moved into a senior advisor role. Doug is passionate about bringing creative solutions to address social problems and achieving big positive change in the world.